Cross-posted to Cavmaths here.

Earlier this week I wrote this post on mathematical elegance and whether or not it should have marks awarded to it in A level examinations, then bizarrely the next day in my GCSE class I came across a question that could be answered many ways. In fact it was answered in a few ways by my own students.

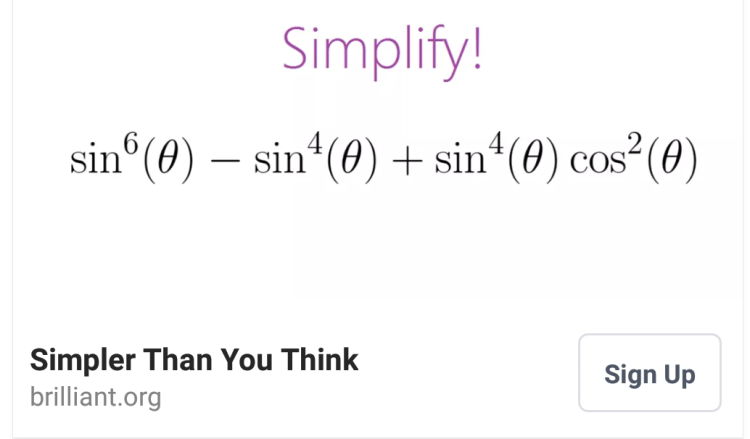

Here’s the question – it’s from the November Edexcel Non-calculator higher paper:

I like this question, and am going to look at the two ways students attempted it and a third way I think I would have gone for. Before you read in I’d love it if you have a think about how you would go about it and let me know.

Method 1

Before I go into this method I should state that the students weren’t working through the paper, they were completing some booklets I’d made based on questions taken from towards the end of recent exam papers q’s I wanted them to get some practice working on the harder stuff but still be coming at the quite cold (ie not “here’s a booklet on sine and cosine rule, here’s one on vectors,” etc). As these books were mixed the students had calculators and this student hadn’t noticed it was marked up as a non calculator question.

He handed me his worked and asked to check he’d got it right. I looked, first he’d used the equation to find points A (3,0) and D (0,6) by subbing 0 in for y and x respectively. He then used right angled triangle trigonometry to work out the angle OAD, then worked out OAP from 90 – OAD and used trig again to work out OP to be 1.5, thus getting the correct answer of 7.5. I didn’t think about the question too much and I didn’t notice that it was marked as non-calculator either. I just followed his working, saw that it was all correct and all followed itself fine and told him he’d got the correct answer.

Method 2

Literally 2 minutes later another student handed me her working for the same question and asked if it was right, I looked and it was full of algebra. As I looked I had the trigonometry based solution in my head so starter to say “No” but then saw she had the right answer so said “Hang on, maybe”.

I read the question fully then looked at her working. She had recognised D as the y intercept of the equation so written (0,6) for that point then had found A by subbing y=0 in to get (3,0). Next she had used the fact that the product of two perpendicular gradients is -1 to work put the gradient of the line through P and A is 1/2.

She then used y = x/2 + c and point A (3,0) to calculate c to be -1/2, which she recognised as the Y intercept, hence finding 5he point P (0,-1.5) it then followed that the answer was 7.5.

A lovely neat solution I thought, and it got me thinking as to which way was more elegant, and if marks for style would be awarded differently. I also thought about which way I would do it.

Method 3

I’m fairly sure that if I was looking at this for the first time I would have initially thought “Trigonometry”, then realised that I can essential bypass the trigonometry bit using similar triangles. As the axes are perpendicular and PAD is a right angle we can deduce that ODA = OAP and OPA = OAD. This gives us two similar triangles.

Using the equation as in both methods above we get the lengths OD = 6 and OA = 3. The length OD in triangle OAD corresponds to the OA in OAP, and OD on OAD corresponds to OP, this means that OP must be half of OA (as OA is half of OD) and is as such 1.5. Thus the length PD is 7.5.

Method 4

This question had me intrigued, so i considered other avenues and came up with Pythagoras’s Theorem.

Obviously AD^2 = 6^2 + 3^2 = 45 (from the top triangle). Then AP^2 = 3^2 + x^2 (where x = OP). And PD = 6 + x so we get:

(6 + x)^2 = 45 + 9 + x^2

x^2 + 12x + 36 = 54 + x^2

12x = 18

x = 1.5

Leading to a final answer of 7.5 again.

Another nice solution. I don’t know which I like best, to be honest. When I looked at the rest of the class’s work it appears that Pythagoras’s Theorem was the method that was most popular, followed by trigonometry then similar triangles. No other student had used the perpendicular gradients method.

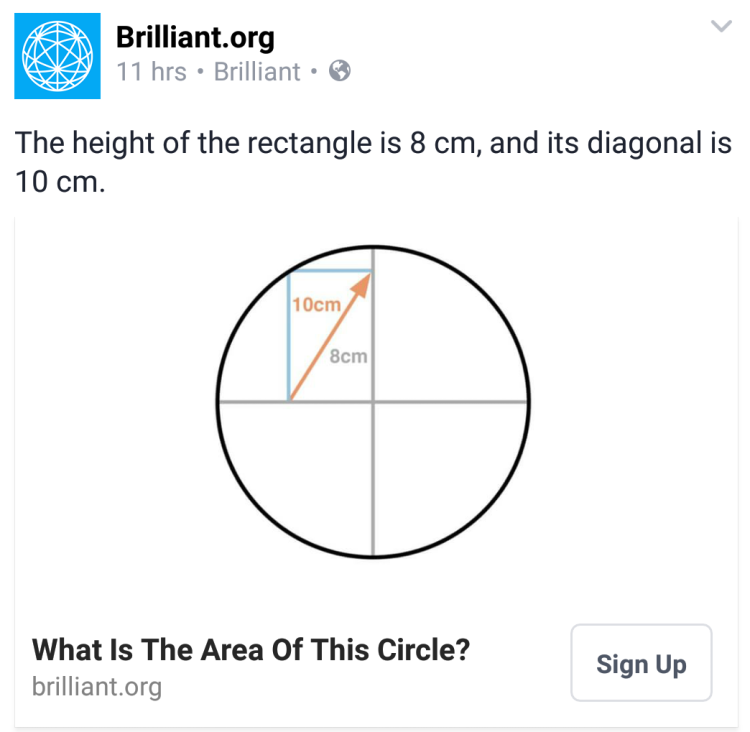

I thought it might be interesting to check the mark scheme:

All three methods were there (obviously the trig method was missed due to it being a non calculator paper). I wondered if the ordering of the mark scheme suggested the preference of the exam board, and which solution they find more elegant. I love all the solutions, and although I think similar triangles is the way I’d go at it if OD not seen it, I think I prefer the perpendicular gradients method.

Did you consider this? Which way would you do the question? Which way would your students? Do you tuink one is more elegant? Do you think that matters? I’d love to know, and you can tell me in the comments or via social media!